About the Author:

James M. McPherson is George Henry Davis '86 Professor of American History at Princeton University, where he has taught since 1962. He is the author of a dozen books, mostly on the era of the American Civil War. His Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era won the Pulitzer Prize in History in 1989, and his For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War won the Lincoln Prize in 1998. Alan Brinkley is Allan Nevins Professor of History at Columbia University, where he has taught since 1991. His works include Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression (1982), which won the National Book Award; The Unfinished Nation: A Concise History of the American People (1993); The End of Reform: New Deal Liberalism in Recession and War (1995); and Liberalism and Its Discontents (1998). The Society of American Historians was founded in 1939 by Allan Nevins and several fellow authors for the purpose of promoting literary distinction in historical writing. From its inception, the Society has sought ways to bring good historical writing to the largest possible audience. Membership in the society is by invitation only and is limited to 250 authors. The Society administers four awards: the annual Francis Parkman Prize for the best-written nonfiction book on American history, the annual Allan Nevins Prize for the best-written dissertation on an important theme in American history, the biannual Bruce Catton Prize for lifetime achievement in historical writing, and the biannual James Fenimore Cooper Prize for the best historical novel.

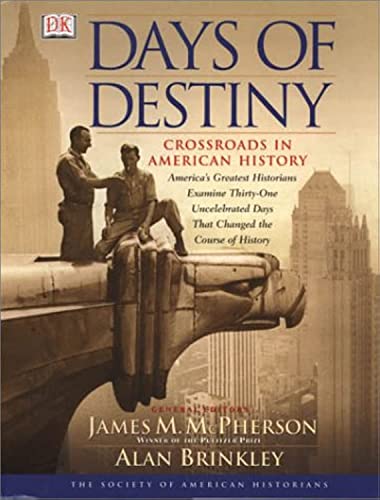

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

September 13, 1862 The Lost Orders by James M. McPherson Saturday, September 13, 1862, was far from an ordinary late summer day for Cpl. Barton W. Mitchell of the Twenty-seventh Indiana Volunteer Infantry. Early that morning, his regiment had been ordered to stack arms and take a break in a meadow just east of Frederick, Maryland. The Twenty-seventh was part of the XII Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Its soldiers had experienced hard fighting and marching that summer, though they had not been present two weeks earlier at the second battle of Bull Run (or Manassas, as the Confederates called it). The Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan was now probing toward the South Mountain gaps in western Maryland, looking for Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Lee had invaded Maryland a week earlier in a climactic effort to conquer a peace, and part of his army had camped four days earlier in the very field where Corporal Mitchell and his buddy, Sgt. John M. Bloss, flopped down in the welcome shade of trees along a fence line. September 13 was a sultry day, and the two tired soldiers hoped to catch forty winks before their regiment resumed its march. As he turned over, however, Mitchell noticed a bulky envelope lying in some tall grass nearby. Curious, he picked it up and discovered inside a sheet of paper wrapped around three cigars. As Bloss went off to hunt for a match, Mitchell noticed that the paper contained writing under the heading "Headquarters, Army of Northern Virginia, Special Orders, No. 191" and was dated September 9. This caught his surprised attention, and his eyes grew wider as he read through the orders studded with names that Northern soldiers knew all too well--Jackson, Longstreet, Stuart--and signed "R. H. Chilton, Assist. Adj.-Gen. By command of Gen. R. E. Lee." "As I read, each line became more interesting," Mitchell said later. "I forgot those cigars." Bloss and Mitchell took the document to their captain, who excitedly passed it on to his regimental commander, who took it to Col. Samuel E. Pittman, division headquarters adjutant. By an extraordinary coincidence, Pittman had known R. H. Chilton in the prewar U.S. Army and recognized his handwriting. The orders were genuine. Pittman rushed to McClellan's headquarters and showed him the paper. According to one report, the Union commander exclaimed after reading Lee's orders, "Now I know what to do!" In a telegram to Pres. Abraham Lincoln dated noon on September 13, McClellan reported, "I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it.... I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap." McClellan's elation proved to be overly optimistic, in part because his own movements in response to this remarkable windfall were characteristically slow and cautious. Nevertheless, Maj. Walter J. Taylor of Lee's staff referred after the war to the significance of these lost orders: "The God of battles alone knows what would have occurred but for the singular accident mentioned; it is useless to speculate on this point, but certainly the loss of this battle-order constitutes one of the pivots on which turned the event of the war." By "the event of the war," Taylor meant the battle of Antietam (called Sharpsburg by the South), which occurred four days later. The loss and finding and verification of Lee's orders certainly was a "singular accident"; the odds against such a chain of coincidences occurring must have been a million to one. Yet it did occur, and this sequence of events became, according to Taylor, "one of the pivots" on which both the battle and the war turned. What were these orders? How were they lost? Why were they so important? To answer these questions, we must turn back the clock several months. During the first half of 1862, Union arms had won a string of victories along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts as well as in the river systems of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In addition, the North had consolidated its control of Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and western Virginia (soon to become the new state of West Virginia). In eastern Virginia, the Army of the Potomac had advanced up the peninsula between the York and James Rivers to within six miles of Richmond. By June 1862, the days of the Confederacy seemed numbered. But that month, Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia and Braxton Bragg took over the Army of Tennessee. Both men immediately launched counteroffensives that, within three months, took their armies from imminent defeat to imminent success, with Bragg invading Kentucky and Lee crossing the Potomac into Maryland after winning major victories in the Seven Days' Campaign (June 25-July 1) and at Second Manassas (August 29-30). This startling reversal of momentum caused Northern morale to plummet. "The feeling of despondency is very great," one friend of McClellan wrote after the Seven Days' battles. Reacting to this decline in spirits, Lincoln lamented, "It seems unreasonable that a series of successes, extending through half a year, and clearing more than a hundred thousand square miles of country, should help us so little, while a single half-defeat [the Seven Days' Campaign] should hurt us so much." Unreasonable or not, it was a fact. The peace wing of the Democratic party stepped up its attacks on Lincoln's policy of trying to restore the Union by war. Branded disloyal Copperheads by Republicans, these Peace Democrats had long insisted that Northern armies could never conquer the South and that the government should seek an armistice and peace negotiations. Confederate military success during the summer of 1862 boosted the credibility of these arguments. Rather than give up and negotiate a peace, however, Lincoln and the Republican Congress acted to intensify the war dramatically. In July, the president called for three hundred thousand more three-year volunteers; meanwhile, Congress passed a militia act that required the states to provide specified numbers of nine-month militia and imposed a draft to make up any deficiencies in the quotas. The same day (July 17) that Lincoln signed this militia bill, he also signed a confiscation act punishing treasonous Confederates by seizing their property, including their slaves. Slaves constituted the principal labor force in the Southern economy. Thousands built fortifications, hauled supplies, and performed fatigue labor for Confederate armies. From the onset of the war, radical Republicans who understood this had urged a policy of emancipation. Such a blow, they believed, would strike at the heart of the rebellion and convert the slaves' labor from a Confederate to a Union asset. By the summer of 1862, Lincoln had come to agree with them. But he doubted the constitutionality and effectiveness of congressional confiscation, a cumbersome process that would have required proof in court that a given slaveholder had engaged in "rebellion." At the same time, he believed that, as commander in chief, he had the power during time of war to seize enemy property being used to perpetuate hostilities against the United States. Slaves were such property. Therefore, on July 22, Lincoln told his cabinet that he intended to issue an emancipation proclamation as a "military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.... Decisive and extensive measures must be adopted.... The slaves [are] undoubtedly an element of strength to those who [have] their service, and we must decide whether that element should be with us or against us." Most of the cabinet agreed, but Secretary of State William H. Seward advised postponement of the edict "until you can give it to the country supported by military success." Otherwise, Seward argued, the world might view the president's proclamation "as the last measure of an exhausted government, a cry for help... our last shriek on the retreat." This advice persuaded Lincoln to await a more propitious moment, but when that moment might come was anyone's guess. With the Confederate invasions of Maryland and Kentucky that fall, Northern morale fell even lower. "The nation is rapidly sinking just now," New York lawyer George Templeton Strong wrote in early September. "Stonewall Jackson (our national bugaboo) about to invade Maryland, 40,000 strong. General advance of the rebel line threatening our hold on Missouri and Kentucky.... Disgust with our present government is certainly universal." Democrats hoped to capitalize on this disgust in the November congressional elections, and Republicans feared the prospect. "After a year and a half of trial," wrote one, "and a pouring out of blood and treasure, and the maiming and death of thousands, we have made no sensible progress in putting down the rebellion... and the people are desirous of some change." The Republican majority in the House was vulnerable. Although there were 105 Republicans to just 43 Democrats, 30 other seats belonged to border-state Unionists who sometimes voted with the Democrats. Thus, even the normal loss of seats in an off-year election might endanger the Republican majority--and 1862 was scarcely a normal year. With Confederate invaders in two border states ripe for the plucking and Lee threatening Pennsylvania, Democrats seemed likely to gain control of the House with their platform of an armistice and peace negotiations. Such an outcome, Lincoln knew, would cripple the Northern war effort. Robert E. Lee was also well aware of the Northern political situation. It was one of the factors that had prompted his decision to go ahead with the invasion of Maryland despite the poor physical condition of his army after ten weeks of constant marching and fighting that had produced thirty-five thousand Confederate casualties and thousands more stragglers. "The present posture of affairs," Lee wrote Confederate president Jefferson Davis on September 8 from his headquarters near Frederick, "places it in [our] power... to propose [to the U.S. government] the recognition of our independence." Such a "proposal of peace," Lee declared, "would enable the people of the United States to determine at their coming elections whether they will support those who favor a prolongation of the war, or those who wish to bring it to a termination." Lee didn't mention the foreign policy implications of his invasion, though these were considerable as well. Newspapers in the North and South, as well as in Britain, were full of rumors and reports of imminent British and French intervention to end the American war. At the very least, it was believed, these two nations would soon be granting diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy. The Union naval blockade of the Confederate coastline had interrupted cotton exports to Europe, shutting down textile factories and throwing thousands out of work in Britain and France. An end to the fighting would reopen foreign trade and bring a renewed flow of cotton from the South. Beyond these commercial reasons, powerful leaders and portions of the public in both countries sympathized with the South. When news of the Seven Days' battles reached Paris, for example, Emperor Napoleon III instructed his foreign minister, "Demandez au gouvernement anglais s'il ne croit pas le moment venu de reconnaître le Sud." British sentiment also seemed to be moving in this direction. The U.S. consul in Liverpool reported that "we are in more danger of intervention than we have been at any previous period.... They are all against us and would rejoice at our downfall." The Confederate envoy in London, James Mason, anticipated "intervention speedily in some form." News of Second Manassas and the invasions of Maryland and Kentucky strengthened the Confederate cause abroad. Early that fall at Newcastle, Britain's chancellor of the exchequer gave a speech in which he declared that "Jefferson Davis and other leaders have made an army; they are making, it appears, a navy; and they have made what is more than either; they have made a nation." More cautiously, the British prime minister, Viscount Palmerston, and his foreign secretary, John Russell, discussed a plan under which Britain and France would offer mediation to end the war on the basis of Confederate independence--if Lee's invasion of Maryland brought another Confederate victory. Union forces "got a complete smashing" at Second Bull Run, wrote Palmerston to Russell on September 14, "and it seems not altogether unlikely that still greater disasters await them, and that even Washington or Baltimore may fall into the hands of the Confederates. If this should happen, would it not be time for us to consider whether in such a state of things England and France might not address the contending parties and recommend an arrangement on the basis of separation?" Russell concurred and added that if the North refused the offer of mediation, "we ought ourselves to recognize the Southern States as an independent State." Northern leaders were certainly alarmed by the political and diplomatic dangers provoked by Lee's invasion, but even more pressing was the military crisis. The Union force that had lost Second Bull Run was an ill-matched amalgam of troops from Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's IX Corps (transferred from North Carolina), and parts of McClellan's Army of the Potomac (transferred from the failed Peninsular Campaign). McClellan disliked Pope and was sulking because he had been forced to withdraw from the peninsula. This caused him to drag his feet when ordered to send troops to Pope's aid and also influenced the conduct of his subordinates. Two of his strongest corps, for example, although within hearing of the guns along Bull Run, never made it to the battlefield. Lincoln considered McClellan's behavior "unpardonable," and a majority of the cabinet wanted him to cashier the general. But Lincoln also recognized McClellan's organizational skills and the remarkable hold he had on the affections of the army, which had been demoralized by its recent defeats. The president therefore gave McClellan command of all Union troops in the theater with instructions to meld them into the Army of the Potomac and move out to fight the invaders. To those cabinet members who protested, Lincoln conceded that McClellan had "acted badly in this matter," but "he has the Army with him.... We must use what tools we have. There is no man in the Army who can lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he." Events confirmed Lincoln's judgment. A junior officer wrote that when the soldiers learned of McClellan's appointment to command the combined forces in and around Washington, "from extreme sadness we passed in a twinkling to a delirium of delight.... Men threw their caps in the air, and danced and frolicked like schoolboys.... The effect of this man's presence upon the Army of the Potomac... was electrical." McClellan indeed reorganized the army and licked it into shape in a strikingly short time. But then he reverted to his wonted caution and tendency to overestimate the strength of his enemy. He clamored for reinforcements, particularly the twelve thousand troops garrisoned at Harpers Perry, but General in Chief Henry W. Halleck refused to release these men. Halleck's refusal created a risky opening for Lee. The Harpers Ferry garrison threatened his line of supply through the Shenandoah Valley, but it was not nearly strong enough to withstand the focused might of his Army of Northern Virginia. So on September 9, Lee dictated those fateful Special Order No. 191, which sent nearly two thirds of his army to Harpers Ferry in three widely separated columns under the overall command of Stonewall Jackson. The opportunity: a large supply of artillery, rifles, ammunition, provisions, shoes, and clothing for his ragged, shoeless, hungry troops. The problem: During the t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.