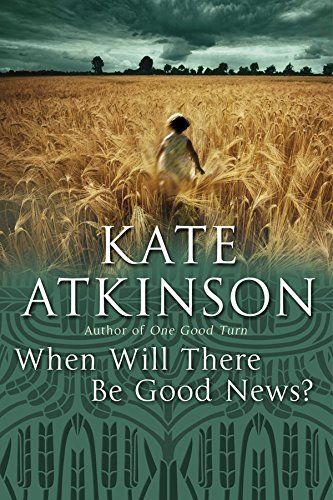

Items related to When Will There Be Good News?

When Will There Be Good News? is the brilliant new novel from the acclaimed author of Case Histories and One Good Turn, once again featuring private investigator Jackson Brodie.

Thirty years ago, six-year-old Joanna witnessed the brutal murders of her mother, brother and sister, before escaping into a field, and running for her life. Now, the man convicted of the crime is being released from prison, meaning Dr. Joanna Hunter has one more reason to dwell on the pain of that day, especially with her own infant son to protect.

Sixteen-year-old Reggie, recently orphaned and wise beyond her years, works as a nanny for Joanna Hunter, but has no idea of the woman’s horrific past. All Reggie knows is that Dr. Hunter cares more about her baby than life itself, and that the two of them make up just the sort of family Reggie wished she had: that unbreakable bond, that safe port in the storm. When Dr. Hunter goes missing, Reggie seems to be the only person who is worried, despite the decidedly shifty business interests of Joanna’s husband, Neil, and the unknown whereabouts of the newly freed murderer, Andrew Decker.

Across town, Detective Chief Inspector Louise Monroe is looking for a missing person of her own, murderer David Needler, whose family lives in terror that he will return to finish the job he started. So it’s not surprising that she listens to Reggie’s outrageous thoughts on Dr. Hunter’s disappearance with only mild attention. But when ex-police officer and Private Investigator, Jackson Brodie arrives on the scene, with connections to Reggie and Joanna Hunter of his own, the details begin to snap into place. And, as Louise knows, once Jackson is involved there’s no telling how many criminal threads he will be able to pull together — or how many could potentially end up wrapped around his own neck.

In an extraordinary virtuoso display, Kate Atkinson has produced one of the most engrossing, masterful, and piercingly insightful novels of this or any year. It is also as hilarious as it is heartbreaking, as Atkinson weaves in and out of the lives of her eccentric, grief-plagued, and often all-too-human cast. Yet out of the excesses of her characters and extreme events that shake their worlds comes a relatively simple message, about being good, loyal, and true. When Will There Be Good News? shows us what it means to survive the past and the present, and to have the strength to just keep on keeping on.

From the Hardcover edition.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

In the Past

Harvest

The heat rising up from the tarmac seemed to get trapped between the thick hedges that towered above their heads like battlements.

‘Oppressive,’ their mother said. They felt trapped too. ‘Like the maze at Hampton Court,’ their mother said. ‘Remember?’

‘Yes,’ Jessica said.

‘No,’ Joanna said.

‘You were just a baby,’ their mother said to Joanna. ‘Like Joseph is now.’ Jessica was eight, Joanna was six.

The little road (they always called it ‘the lane’) snaked one way and then another, so that you couldn’t see anything ahead of you. They had to keep the dog on the lead and stay close to the hedges in case a car ‘came out of nowhere’. Jessica was the eldest so she was the one who always got to hold the dog’s lead. She spent a lot of her time training the dog, ‘Heel!’ and ‘Sit!’ and ‘Come!’ Their mother said she wished Jessica was as obedient as the dog. Jessica was always the one who was in charge. Their mother said to Joanna, ‘It’s all right to have a mind of your own, you know. You should stick up for yourself, think for yourself,’ but Joanna didn’t want to think for herself.

The bus dropped them on the big road and then carried on to somewhere else. It was ‘a palaver’ getting them all off the bus. Their mother held Joseph under one arm like a parcel and with her other hand she struggled to open out his newfangled buggy. Jessica and Joanna shared the job of lifting the shopping off the bus. The dog saw to himself. ‘No one ever helps,’ their mother said. ‘Have you noticed that?’ They had.

‘Your father’s country fucking idyll,’ their mother said as the bus drove away in a blue haze of fumes and heat. ‘Don’t you swear,’ she added automatically, ‘I’m the only person allowed to swear.’

They didn’t have a car any more. Their father (‘the bastard’) had driven away in it. Their father wrote books, ‘novels’. He had taken one down from a shelf and shown it to Joanna, pointed out his photograph on the back cover and said, ‘That’s me,’ but she wasn’t allowed to read it, even though she was already a good reader. (‘Not yet, one day. I write for grown-ups, I’m afraid,’ he laughed. ‘There’s stuff in there, well . . .’)

Their father was called Howard Mason and their mother’s name was Gabrielle. Sometimes people got excited and smiled at their father and said, ‘Are you the Howard Mason?’ (Or sometimes, not smiling, ‘that Howard Mason’ which was different although Joanna wasn’t sure how.)

Their mother said that their father had uprooted them and planted them ‘in the middle of nowhere’. ‘Or Devon, as it’s commonly known,’ their father said. He said he needed ‘space to write’ and it would be good for all of them to be ‘in touch with nature’. ‘No television!’ he said as if that was something they would enjoy.

Joanna still missed her school and her friends and Wonder Woman and a house on a street that you could walk along to a shop where you could buy the Beano and a liquorice stick and choose from three different kinds of apples instead of having to walk along a lane and a road and take two buses and then do the same thing all over again in reverse.

The first thing their father did when they moved to Devon was to buy six red hens and a hive full of bees. He spent all autumn digging over the garden at the front of the house so it would be ‘ready for spring’. When it rained the garden turned to mud and the mud was trailed everywhere in the house, they even found it on their bed sheets. When winter came a fox ate the hens without them ever having laid an egg and the bees all froze to death which was unheard of, according to their father, who said he was going to put all those things in the book (‘the novel’) he was writing. ‘So that’s all right then,’ their mother said.

Their father wrote at the kitchen table because it was the only room in the house that was even the slightest bit warm, thanks to the huge temperamental Aga that their mother said was ‘going to be

the death of her’. ‘I should be so lucky,’ their father muttered. (His book wasn’t going well.) They were all under his feet, even their mother.

‘You smell of soot,’ their father said to their mother. ‘And cabbage and milk.’

‘And you smell of failure,’ their mother said.

Their mother used to smell of all kinds of interesting things, paint and turpentine and tobacco and the Je Reviens perfume that their father had been buying for her since she was seventeen years old and ‘a Catholic schoolgirl’, and which meant ‘I will return’ and was a message to her. Their mother was ‘a beauty’ according to their father but their mother said she was ‘a painter’, although she hadn’t painted anything since they moved to Devon. ‘No room for two creative talents in a marriage,’ she said in that way she had, raising her eyebrows while inhaling smoke from the little brown cigarillos she smoked. She pronounced it thigariyo like a foreigner. When she was a child she had lived in faraway places that she would take them to one day. She was warm-blooded, she said, not like their father who was a reptile. Their mother was clever and funny and surprising and nothing like their friends’ mothers. ‘Exotic’, their father said.

The argument about who smelled of what wasn’t over apparently because their mother picked up a blue-and-white-striped jug from the dresser and threw it at their father, who was sitting at the table staring at his typewriter as if the words would write themselves if he was patient enough. The jug hit him on the side of the head and he roared with shock and pain. With a speed that Joanna could only admire, Jessica plucked Joseph out of his high-chair and said, ‘Come on,’ to Joanna and they went upstairs where they tickled Joseph on the double bed that Joanna and Jessica shared. There was no heating in the bedroom and the bed was piled high with eiderdowns and old coats that belonged to their mother. Eventually all three of them fell asleep, nestled in the mingled scents of damp and mothballs and Je Reviens.

When Joanna woke up she found Jessica propped up on pillows, wearing gloves and a pair of earmuffs and one of the coats from the bed, drowning her like a tent. She was reading a book by torchlight.

‘Electricity’s off,’ she said, without taking her eyes off the book. On the other side of the wall they could hear the horrible animal noises that meant their parents were friends again. Jessica silently offered Joanna the earmuffs so that she didn’t have to listen.

When the spring finally came, instead of planting a vegetable garden, their father went back to London and lived with ‘his other woman’ — which was a big surprise to Joanna and Jessica, although not apparently to their mother. Their father’s other woman was called Martina — the poet — their mother spat out the word as if it was a curse. Their mother called the other woman (the poet) names that were so bad that when they dared to whisper them (bitch-cunt-whore-poet) to each other beneath the bedclothes they were like poison in the air.

Although now there was only one person in the marriage, their mother still didn’t paint.

They made their way along the lane in single file, ‘Indian file’, their mother said. The plastic shopping bags hung from the handles of the buggy and if their mother let go it tipped backwards on to the ground.

‘We must look like refugees,’ she said. ‘Yet we are not downhearted,’ she added cheerfully. They were going to move back into town at the end of the summer, ‘in time for school’.

‘Thank God,’ Jessica said, in just the same way their mother said it.

Joseph was asleep in the buggy, his mouth open, a faint rattle from his chest because he couldn’t shake off a summer cold. He was so hot that their mother stripped him to his nappy and Jessica blew on the thin ribs of his little body to cool him down until their mother said, ‘Don’t wake him.’

There was the tang of manure in the air and the smell of the musty grass and the cow parsley got inside Joanna’s nose and made her sneeze.

‘Bad luck,’ her mother said, ‘you’re the one that got my allergies.’ Their mother’s dark hair and pale skin went to her ‘beautiful boy’ Joseph, her green eyes and her ‘painter’s hands’ went to Jessica. Joanna got the allergies. Bad luck. Joseph and their mother shared a birthday too although Joseph hadn’t had any birthdays yet. In another week it would be his first. ‘That’s a special birthday,’ their mother said. Joanna thought all birthdays were special.

Their mother was wearing Joanna’s favourite dress, blue with a pattern of red strawberries. Their mother said it was old and next summer she would cut it up and make something for Joanna out of it if she liked. Joanna could see the muscles on her mother’s tanned legs moving as she pushed the buggy up the hill. She was strong. Their father said she was ‘fierce’. Joanna liked that word. Jessica was fierce too. Joseph was nothing yet. He was just a baby, fat and happy. He liked oatmeal and mashed banana, and the mobile of little pap...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAudiobooks

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 1846572401

- ISBN 13 9781846572401

- BindingAudio CD

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 6.00

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

When Will There Be Good News?: (Jackson Brodie)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. In rural Devon, six-year-old Joanna Mason witnesses an appalling crime. Thirty years later the man convicted of the crime is released from prison. In Edinburgh, sixteen-year-old Reggie works as a nanny for a G.P. But Dr Hunter has gone missing and Reggie seems to be the only person who is worried. Across town, Detective Chief Inspector Louise Monroe is also looking for a missing person, unaware that hurtling towards her is an old friend -- Jackson Brodie -- himself on a journey that becomes fatally interrupted. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # GOR007240084