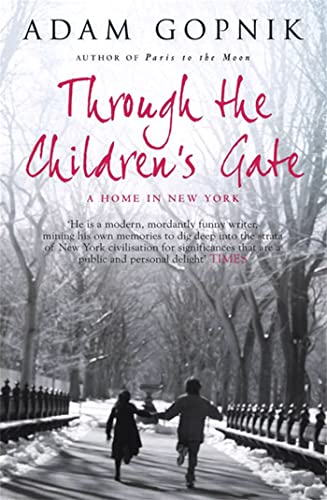

Items related to Through The Children's Gate: A Home in New York

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

In the fall of 2000, just back from Paris, with the sounds of its streets still singing in my ears and the codes to its courtyards still lining my pockets, I went downtown and met a man who was making a perfect map of New York. He worked for the city, and from a set of aerial photographs and underground schematics he had turned every block, every highway, and every awning—every one in all five boroughs!—into neatly marked and brightly colored geometric spaces laid out on countless squares. Buildings red, streets blue, open spaces white, the underground tunnels sketched in dotted lines . . . everything in New York was on the map: every ramp to the Major Deegan Expressway and every abandoned brownstone in the Bronx.

The kicker was that the maniacally perfect map was unfinished and even unfinishable, because the city it described was too “dynamic,” changing every day in ways that superceded each morning’s finished drawing. Each time everything had been put in place—the subway tunnels aligned with the streets, the Con Ed crawl spaces with the subway tunnels, all else with the buildings above—someone or other would come back with the discouraging news that something had altered, invariably a lot. So every time he was nearly done, he had to start all over.

I keep a small section of that map in my office as a reminder of several New York truths. The first is that an actual map of New York recalls our inner map of the city. We can’t make any kind of life in New York without composing a private map of it in our minds—and these inner maps are always detailed, always divided into local squares, and always unfinished. The private map turns out to be as provisional as the public one—not one on which our walks and lessons trace grooves deepening over the years, but one on which no step, no thing seems to leave a trace. The map of the city we carried just five years ago hardly corresponds to the city we know today, while the New Yorks we knew before that are buried completely. The first New York I knew well, Soho’s art world of twenty years ago, is no less vanished now than Carthage; the New York where my wife and I first set up housekeeping, the old Yorkville of German restaurants and sallow Eastern European families, is still more submerged, Atlantis; and the New York of our older friends—where the light came in from the river and people wore hats and on hot nights slept in Central Park—is not just lost but by now essentially fictional, like Nu. New York is a city of accommodations and of many maps. We constantly redraw them, whether we realize it or not, and are grateful if a single island we knew on the last survey is still to be found above water.

I knew this, or sensed some bit of it, the first time I ever saw the city. This was in 1959, when my parents, art-loving Penn students, brought my sister and me all the way from Philadelphia to see the new Guggenheim Museum on its opening day. My family had passed through New York a half century earlier, on the way to Philadelphia. My grandfather, like every other immigrant, entered through Ellis Island, still bearing, as family legend has it, the Russian boy’s name of “Lucie,” which I suppose now was the Russianized form of the Yiddish Louis, actually, same as his father’s. The immigration officer explained with, as I always imagined it, a firm but essentially charitable brusqueness that you couldn’t call a boy Lucy in this country. “What shall we call the boy, then?” his baffled and exhausted parents asked. The immigration officer looked around the great hall and drew the quick conclusion. “Call him Ellis,” he said, and indeed my grandfather lived and died in honor of the New York island as Ellis Island Gopnik. Well, as Ellis Gopnik, anyway—though Ellis was regarded as a touch too New York for Philadelphia, and Lucie-Ellis actually lived and died known to all as Al.

For the Guggenheim occasion, my mother had sewn a suit of mustard-colored velvet for me and a matching dress for my sister, and we stood in line outside the corkscrew building, trying to remember what we had been taught about Calder. Afterward, we marched down the ramp of the amazing museum and then walked along Fifth Avenue, where we saw a Rolls-Royce. We ate dinner at a restaurant that served a thrilling, exotic mix of blintzes and insults, and that night we slept in my aunt Hannah’s apartment at Riverside Drive and 115th Street. A perfect day.

I remember looking out the window of the little maid’s room where we had been installed, seeing the lights of the Palisades across the way, and thinking, There! There it is! There’s New York, this wonderful city. I’ll go live there someday. Even being in New York, the actual place, I found the idea of New York so wonderful that I could only imagine it as some other place, greater than any place that would let me sleep in it—a distant constellation of lights I had not yet been allowed to visit. I had arrived in Oz only to think, Well, you don’t live in Oz, do you?

Ever since, New York has existed for me simultaneously as a map to be learned and a place to be aspired to—a city of things and a city of signs, the place I actually am and the place I would like to be even when I am here. As a kid, I grasped that the skyline was a sign that could be, so to speak, relocated to New Jersey—a kind of abstract, receding Vision whose meaning would always be “out of reach,” not a concrete thing signifying “here you are.” Even when we are established here, New York somehow still seems a place we aspire to. Its life is one thing—streets and hot dogs and brusqueness—and its symbols, the lights across the way, the beckoning skyline, are another. We go on being inspired even when we’re most exasperated.

If the energy of New York is the energy of aspiration—let me in there!—the spirit of New York is really the spirit of accommodation—I’ll settle for this. And yet both shape the city’s maps, for what aspi- rations and accommodations share is the quality of becoming, of not being fixed in place, of being in every way unfinished. An aspira- tion might someday be achieved; an accommodation will someday be replaced. The romantic vision—we’ll get to the city across the river someday!—ends up harmonizing with the unromantic embrace of reality: We’ll get that closet cleaned out yet.

In New York, even monuments can fade from your mental map under the stress of daily life. I can walk to the Guggenheim if I want to, these days, but in my mind it has become simply a place to go when the coffee shops are too full, a corkscrew Three Guys, an alternative place to get a cappuccino and a bowl of bean soup. Another day, suddenly turning a corner, I discover the old monument looking just as it did the first time I saw it, the amazing white ziggurat on a city block, worth going to see.

This doubleness has its romance, but it also has its frustrations. In New York, the space between what you want and what you’ve got creates a civic itchiness: I don’t know a content New Yorker. Complacency and self-satisfaction, the Parisian vices, are not present here, except in the hollow form of competitive boasting about misfortune. (Even the very rich want another townhouse but move into an apartment, while an exclusive subset of the creative class devotes itself to dreaming up things for the super-rich to want, if only so they alone will not be left without desire.)

I went back to New York on many Saturdays as a child, to look at art and eat at delis, and it was, for me, not only the Great Romantic Place but the obvious engine of the working world. After a long time away, I returned, and then in 1978 I returned with the girl I loved. We spent a miraculous day: Bloomingdale’s, MoMA, dinner at Windows on the World, and then the Carnegie Tavern, to hear the matchless poet Ellis Larkins on the piano, just the two of us and Larkins in a cool, mostly empty room. (A quarter century later, I haven’t had another day that good.) We were dazzled by the avenues and delighted by the spires of the Chrysler Building, and we decided that, come what might, we had to get there.

For all that the old pilgrimage of the young and writerly to Manhattan had become, in those years, slightly Quixotic, we determined nevertheless to make it—not drawn to the city romantically, as we were then and later to the idea of Paris, but compelled toward it almost feverishly—deliriously, if you like—as the place you needed to be in order to stake a claim to being at all. This feeling has never left me. I’ve lived elsewhere, but nowhere else feels so entirely, so delusionally—owing more to the full range of emotional energies it possesses than to the comforts it provides—like home.

A home in New York! However will we have one? The exclamation of hope is followed at once by the desperate, the impossible, question. The idea of a home in Manhattan seems at once self-evident and still just a touch absurd, somehow close to a contradiction in its own shaky terms, so that to state it, even quietly, is to challenge some inner sense of decorum, literary if not entirely practical. In literature, after all, New York is where we make careers, deals, compromises, have breakdowns and break-ins and breaks, good and bad. But in reality what we all make in Manhattan are homes (excepting, of course, the unlucky, who don’t, or can’t, and act as a particularly strong reproach to those of us who do). The Life is the big, Trumpish unit of measure in New York, but the home, the apartment with its galley kitchen and the hallways with its cooking smells, is the real measure, the one we know, and all we know. We make as many homes in New York as in any other place. To make a home at all in New York is the tricky part, the hard part, and yet, at the same time, the self-evident part. Millions of other people are doing it, too. Look out your window. “Do New York!” Henry James implored Edith Wharton in a famous letter, meaning encompass it, if you can, but when we try to do New York, it does us and sends us reeling back home. (When the great James tried to come back home to do it, what he did was the house on Fourteenth Street where he was born, and the other homes, around the corner on Sixth.)

I still recall our first efforts at making a home, when my wife and I arrived on a bus from Canada and moved into a single nine-by-eleven basement room, on Eighty-seventh Street. I remember it, exactly a quarter century after, with something approaching disbelief: How did we use so many toggle bolts on three walls? But doing it a second time doesn’t seem easier, or more supple; I can’t walk into a housewares store in Manhattan without feeling myself the victim of a complicated confidence trick, a kind of cynical come-on. We’re really going to use a toaster and a coffee-maker every morning? And then, of course, we do, just like they do in Altoona, just like we did . . . back home.

To make a home in New York, we first have to find a place on the map of the city to make it in. The map alone teaches us lessons about the kind of home you can make. The first New York home we made was in one of the small basement apartments strung along First Avenue. Then there was Soho in its Silver Age, when the cheese counter at Dean & Deluca and the art at Mary Boone conspired to convince one that a Cultural Moment was under way. But that era has passed—a world gone right under, as they all do here—and coming home this time, we hoped to land in one of the more tender squares on the map, the one that kids live in.

We came back to New York in 2000, after years away, to go through the Children’s Gate, and make a home here for good. The Children’s Gate exists, and you really can go through it. It’s the name for the entrance to Central Park at Seventy-sixth Street and Fifth Avenue. The names of the gates—hardly more than openings in the low stone wall describing the park—are among its more poetic, less familiar monuments. In a moment of oddly Ruskinian whimsy, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux gave names to all the entrances of Central Park, calling them gates, each accommodating a class of person to enter there: a park for all the people with entrances for every kind. There was, and is, the Miners’ Gate, and the Scholars’ Gate, and—for a long time this was my favorite—the Strangers’ Gate, high on the West Side. The Children’s Gate is one of the lesser known, though the most inviting of all. On most days you can’t even read its name, since a hot-dog-and-pretzel vendor parks his cart and his melancholy there twelve hours a day, right in front of where the stone is engraved. It’s a shame, actually. For though it’s been a long time since a miner walked through his gate, children really do come in and out of theirs all day and, being children, would love to know about it. Now my family had, in a way, decided to pass through as children, too.

This was true literally—we liked the playground and went there our first jet-lagged morning home—and metaphorically: We had decided to leave Paris for New York for the romance of childhood, for the good of the children. We wanted them to go not to baffling Parisian schools—where they would have gotten a terrific education, been cowed until seventeen, and only then begun to riot—but to a New York progressive school, where they’d get a terrific education and, we hoped, have a good time doing it. Childhood seemed too short to waste on preparation. And we wanted them to grow up in New York, to be natives here, as we could never be, to come in through the Children’s Gate, not the Strangers’ Gate.

A crowd came through the gate with us. Twenty-five years ago, Calvin Trillin could write of his nuclear family of two parents and two kids as being so strange that it was an attraction on bus tours, but by the time we came home, the city had been repopulated—some would say overrun—with children. It was now the drug addicts and transvestites and artists who were left muttering about the undesirable, short element taking over the neighborhood. New York had become, almost comically, a children’s city again, with kiddie-coiffure joints where sex shops had once stood and bare, ruined singles bars turned into play-and-party centers. There was an overrun of strollers so intense that notices forbidding them had to be posted at the entrances of certain restaurants, as previous generations of New Yorkers had warned people not to hitch their horses too close to the curb. There were even special matinees for babies—real babies, not just kids—where the wails of the small could be heard in the dark, in counterpoint to the dialogue of the great Meryl Streep dueting with a wet six-month-old. Whether you thought it was “suburbanized,” “gentrified,” or simply improved, that the city had altered was plain, and the children flooding its streets and parks and schools were the obvious sign.

The transformation of the city, and particularly the end of the constant shaping presence of violent crime, has been amazing, past all prediction, despite the facts that the transformation is not entirely complete and the new city is not entirely pleasing to everyone. Twenty some years ago, it was taken for granted that New York was hell, as Stanley Kauffmann wrote flatly in a review of Ralph Bakshi’s now oddly forgotten New York...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- Publisherriverrun

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 184724324X

- ISBN 13 9781847243249

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Through The Children's Gate (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. On every page of this delicious book you will meet characters and situations that tell you this could only be New York. The parents who are determined to get their children literally to fly at the school production of Peter Pan - the Cambodian cashier at the local deli who is more Jewish than Gopnik's grandfather - his gloriously peculiar analyst who argues that a name can be damaging to the human psyche, saying Adam's name is very ugly - the birder who takes Adam to see the huge flock of feral parrots that have taken over Flatbush. No one knows how they got there or how they survive the brutal winters, but they do. And flourish on it. 'These birds are so bold. They are real New Yorkers. They have so much attitude'. Through the Children's Gate is written with Gopnik's signature mix of mind and heart, elegantly and exultantly alert to the minute miracles that bring a place to life. Adam Gopnik, the highly esteemed, prize winning New Yorker writer, moved his young family back to New York City in 2000. This is a chronicle, by turns tender and hilarious, about raising a family in the middle of Manhattan Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781847243249

Through the Children's Gate

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Language: ENG. Seller Inventory # 9781847243249

Through The Children's Gate: A Home in New York

Book Description Paperback / softback. Condition: New. New copy - Usually dispatched within 4 working days. Adam Gopnik, the highly esteemed, prize winning New Yorker writer, moved his young family back to New York City in 2000. This is a chronicle, by turns tender and hilarious, about raising a family in the middle of Manhattan. Seller Inventory # B9781847243249

Through The Children's Gate: A Home in New York

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 40b958cdc999af75091f1b5b0199e70c

THROUGH THE CHILDREN'S GATE

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 368 pages. 7.80x5.08x0.87 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # __184724324X

Through The Children's Gate: A Home in New York

Book Description Condition: New. 2008. Paperback. . . . . . Seller Inventory # V9781847243249

Through The Children's Gate: A Home in New York

Book Description Condition: New. 2008. Paperback. . . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Seller Inventory # V9781847243249

Through The Children's Gate: A Home in New York

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 6666-HCE-9781847243249

Through The Children's Gate A Home in New York

Book Description PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # HU-9781847243249

Through The Children's Gate (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. On every page of this delicious book you will meet characters and situations that tell you this could only be New York. The parents who are determined to get their children literally to fly at the school production of Peter Pan - the Cambodian cashier at the local deli who is more Jewish than Gopnik's grandfather - his gloriously peculiar analyst who argues that a name can be damaging to the human psyche, saying Adam's name is very ugly - the birder who takes Adam to see the huge flock of feral parrots that have taken over Flatbush. No one knows how they got there or how they survive the brutal winters, but they do. And flourish on it. 'These birds are so bold. They are real New Yorkers. They have so much attitude'. Through the Children's Gate is written with Gopnik's signature mix of mind and heart, elegantly and exultantly alert to the minute miracles that bring a place to life. Adam Gopnik, the highly esteemed, prize winning New Yorker writer, moved his young family back to New York City in 2000. This is a chronicle, by turns tender and hilarious, about raising a family in the middle of Manhattan Shipping may be from our Sydney, NSW warehouse or from our UK or US warehouse, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781847243249